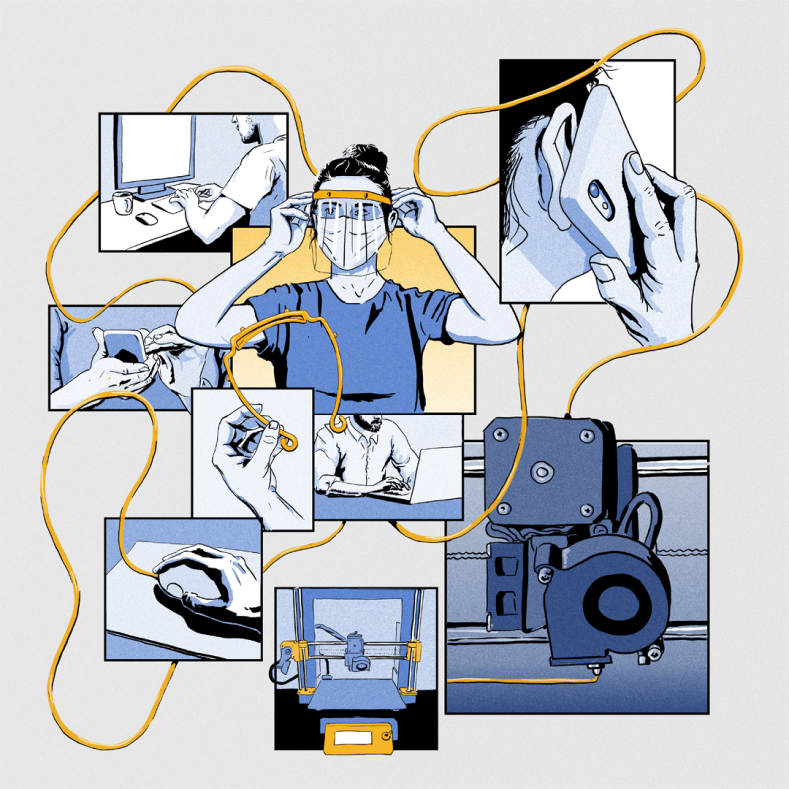

Friday, 1:45pm. My phone dings. If we printed two at a time, we could make a lot more. 3:30pm. Ding. Do you think we could do a stackable version? 6pm. I cook pasta for my family. My phone continues to ding as the water bubbles. Tell the nurses — no chlorine wash — just alcohol for cleaning. It’s late March 2020 and the world is in crisis. I haven’t been on campus in two weeks yet have never felt more connected to my colleagues. Overwhelmed by the big picture, we focus on the immediate. We don’t yet have the distance to be weary. We are running on adrenaline. My phone is stuck to my hand as the messages continue into the night. 10pm. I’m putting on an overnight print.

A couple of days earlier, an old friend reached out to me on Twitter. My brother is a nurse in A&E. They desperately need faceshields. Don’t you do manufacturing or something there in UCD? Or something, yes. I work in a manufacturing research centre. Usually, we figure out how to make things, better. But my friend just wants us to make things, now. I think about the gloomy basement in Engineering, about the row of 3D printers that the research engineers use to create three—dimensional objects in brightly coloured plastic, resin and carbon fibre. I am not in the basement though. I am at home, my work as a science communicator deemed non— essential. I long to be useful. Most of all I long for distraction. I try not to think about my ageing parents, my husband’s looming redundancy and our receding mortgage prospects, or how to occupy our 4—year—old daughter. A message from my boss. You need to talk to the researchers. One or two researchers are already experimenting with making faceshields on a 3D printer. They just want to be useful too. They are can—do people with access to machines that can do. How many of these can you make? I say. Asking for a friend.

We get into a WhatsApp group and the brainstorming begins. I communicate the immediacy of the need. We focus on the problem in front of us. We don’t have to think about the big picture right now. The researchers get to work. They call in colleagues, friends — anyone with a 3D printer or a good idea. They experiment with faceshield designs; we all silently renew our gratitude to the open source movement. A Scandinavian design fits the bill, but it takes 45 minutes to print just one. The A&E nurse tells me they need at least 200 visors, but will take whatever they can get. The engineers rise to the challenge. From separate, socially distanced locations, they research, they experiment, they share their results. Someone suggests printing two, side by side, on each machine. It won’t reduce build time but it will make it easier.

Someone experiments with stacking the visors, like hamburger ingredients — but stacking soon becomes sticking. By the end of the day, there’s good news. They’ve made 50 faceshields. Even better news — they’ve optimised the print time down to 18 minutes. The A&E nurse is over the moon. I’ve always believed in the power of engineering! he texts me. The researchers double down. It becomes a numbers game. It’s the weekend but time is different now. By Sunday night, 300 visors are ready for collection. Connecting is all that I’m doing that’s useful, but at least it’s something. Selfishly, it’s a welcome distraction as my husband’s redundancy becomes a reality. A dark alignment dawns as my partner’s occupation becomes full—time children’s entertainer, leaving me free to connect, connect. Our nexus grows. I start getting visor requests in from hospitals, ambulance services, nursing homes, GPs, blood banks — first locally, then countrywide. My boss takes a call from researchers in Namibia who are trying to do the same thing we are. A UCD colleague wants to bring our faceshields to the Bugisi healthcare centre in Tanzania. Meanwhile, a message from a researcher. UCD is beyond 5km from her home. The Gardai stopped me on my way in to work. But they let me through. We organise letters to help the researchers get through the checkpoints.

Production ramps up; so does recruitment. We talk to our colleagues in other universities, in Dublin and Galway. A youth group in Ballymun starts their own production; teachers around the country retrieve the keys to the engineering classroom and dust off the 3D printer. Bank holidays are ignored. The researchers continue to work all hours. Printing, cleaning, sorting, bagging. Boxing up for collection. I arrange the contactless collections. Which side of Engineering is the front again? The lake side or...? At first, boxes are left outside. It’s a windy day — there’s no chance the swans will end up wearing these, is there? The boxes are moved inside. I never meet the people who collect. A milestone is reached: by the end of May, 5,000 visors have been produced and distributed. Send me a photo from the lab, I ask. The researchers try to take a picture maintaining social distance, their faces hidden by masks and visors. Never mind, I say. I’m sure I’ll see you all soon.

Nexus